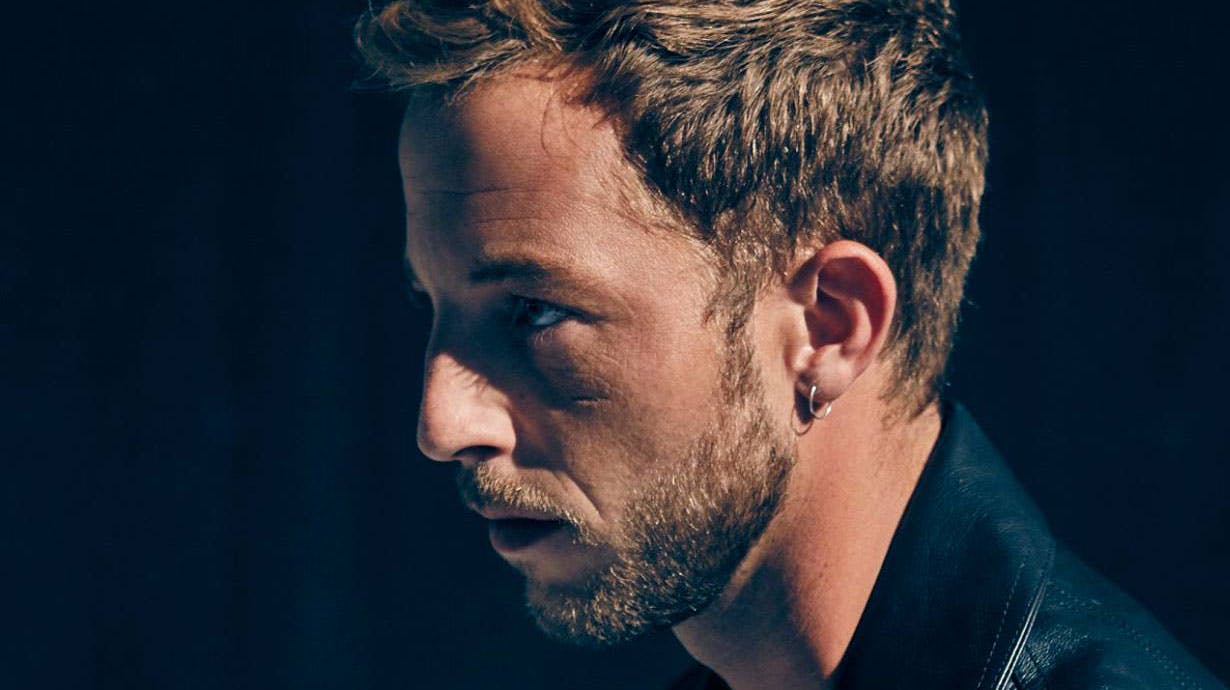

James Morrison

Interview

Four years is your longest break between records yet. Was it a conscious decision to take time out?

Yeah, definitely. I went to a gig to see one of my friends playing with The Specials, and after the gig, Lynval [Golding] said, “Have you got a kid? You should take some time off, man. Because I never took any time off and I’m really gutted that I never got to spend time with my daughter.” And I thought that made a lot of sense: I’d rather live with screwing up my musical career, than live with being a bad dad, you know? So, I took some time out, spent some time with my daughter and it was f***ing great. It was exactly what I needed.

Were there any nerves about taking that time out?

Not at the time. The last thing I wanted to do was think about music; I’d been touring for 18 months on the last album, and my head was f***ed. I haven’t really stopped since I was 21: my first album came out, it went mad, I had to tour it, went straight into the second one, toured it, straight into the third one, my dad died, I took two months out, got straight back on tour for 18 months... So yeah, I needed some time just to not think about records and to come back to myself, think about my family and friends, and do normal things.

So what was the starting point for Higher Than Here? Was there a song that led the way?

The first one that I got was ‘Heaven To A Fool’, and that’s quite ominous and gospel-y. Before I started writing, I knew I wanted [the album] to be darker. I wanted it to capture that part of myself that’s gone through the sh*t and isn’t Mr Positive all the time. In my songs, I always try to be positive and I suppose that can come across a bit cheesy, so I just wanted to get a bit of perspective on life, and not so much sentimentality.

You can hear that in ‘Demons’, definitely. Can you tell us more about the intentions behind that track?

It’s mainly about my own lack of confidence, or me feeling like my upbringing is going to dictate who I’m going to be. I was starting to feel quite depressed before I was writing the album, and I went to see a spiritual healer and she said that I had an evil spirit attached to me. That was why I was feeling bad.

An evil spirit?

Yeah, she said I had a demon attached to me, and I was like, “Right...” I mean, I’m quite spiritual, and I’m open-minded, but even when she was telling me, I thought, “This can’t be real.” She just grabbed it, like grabbing fresh air, and she said it was so big – the biggest one she’d ever dealt with – that she had to open all the windows in the whole building to get it out. And once it went I felt immediately better. I can’t explain it; I just felt better straight away, and I just thought, “Wow, it must be real! I must have had something attached to me that was making me feel bad and making me think sh*t thoughts.” And once that went I associated it with my own personal demons, and the fact that my dad used to always say, “It’s the demons,” if he had a problem with his drink. So it’s my way of saying that I’m not going to get beaten by my demons, like he did.

What other ideas or messages did you want to communicate on Higher Than Here?

Subtly, I wanted it to speak to people who feel a little bit broken or a little bit lost; to give them faith in the world and faith in themselves, in terms of having the strength to go through negative things and come out the other side. I always try to think about the bigger picture; I want my songs to reach everyone, you know? So I try to write songs that will do that, starting from a personal space and try to get it to expand out as big as it can.

But I don’t want to be preachy so I’m really aware of not telling people what to do, like I know all the answers. The lyrical place I’m coming from is, “I’m f***ed and I’m aware of it, and I’m dealing with it.” It’s about being honest with yourself about your flaws, and about the balance between you being lost and found, because you can’t get to a good place without going through something negative. I wanted that journey to be the lyrical underpin, I suppose.

Why did you make ‘Higher Than Here’ the title track? What was the significance of that song?

It was the first song I wrote on the album where I was strident in what I was saying. I just felt like it was the first time I’ve been... not cocky but... adamant that I would be strong enough to take my girlfriend out of a negative place to where she needs to be to feel good. Me and my missus were having a bit of a hard time, so I just tried to write something that is so adamant that I’m going to make it better.

It sounds like it’s been quite a journey, making this album. What are the key things you’ve learned in the process?

I’ve learned that I’m stronger and I’m more resilient than I thought I was. I’ve learned how to be confident in myself, even though I know I’ve got flaws. I guess it’s accepting yourself for who you are; that’s what I’ve accepted, finally, and I’m more proud of who I am than I’ve ever been.

Having a kid really helps that happen. When you’ve got someone that you love more than anyone looking at you like they love you back, it sorts you out. I’m more confident now, and I don’t have that sinking feeling; I feel like I can keep myself afloat.

That sort of self-acceptance often comes with age as well.

Totally. I hated being in my 20s, but as soon as I turned 31, I don’t know... I had to grow up in the limelight, and it was very awkward. I came from a background where I was quiet and I didn’t really get encouraged to be anything other than quiet, so it was a weird transition to then be someone who everyone wants to talk to. Some of this business is bullsh*t and some of it is amazing, an amazing spiritual journey, and I can now see it for what it is.

That ties into the tongue-in-cheek ‘James Morrison vs. The Music Industry’ video you made. How closely do those situations resemble your real life experiences?

I could totally relate to it. I’ve had a lot of meetings about things like remixes and conversations like, “What direction should we go in? How do we get you on Radio 1?” or whatever. So I just thought it was a good way of me taking the p*ss out of while also taking the p*ss out of myself. I’m comfortable enough to take the p*ss now, whereas, before, I just wanted to be taken seriously and I wasn’t being. It did my head in. Now I’m more relaxed about not having to be taken seriously.

The industry must have changed a lot in the 10 years you’ve been making music. Even coming back after four years away must have made a difference?

Yeah, the way that people listen to music and the way that it works in terms of chart positions, it’s all completely changed. But at the same time what else am I going to do? You’ve got to go with it. I’m just happy to be making music, and the fact I’m on my fourth album at 31 is amazing to me; I never thought I’d get past my first album in the beginning. So I just feel grateful and blessed that people still want to listen to my music.

It’s rare to see that kind of longevity nowadays.

Yeah, if you look at who was about when I first came out in terms of singer-songwriters, apart from Paolo [Nutini] and Blunty, there’s not really a lot going on.

But there’s now a whole new breed of successful singer-songwriters, and artists like John Newman and James Bay cite you as an inspiration.

I know! It makes me feel old. Nobody for years said that they liked my music; it wasn’t cool to say you liked James Morrison. So, I suppose, now time’s gone by and I’ve been around a while, they’re more willing to give up compliments.

I’m glad that people nowadays are in the mode of being complimentary, because there was a time when you weren’t allowed to be complimentary of other artists, because it just wasn’t cool. I’ve always tried to be positive about other artists, but now it’s a free-for-all because there’s good music about and we’re all part of it; we all feed into the inspiration machine. Ed Sheeran inspires me, and Paolo Nutini, John Newman and James Bay: we’re all linked but at the same time we’ve got our own space.

How have your motivations for making music changed since you started out?

I just had blind ambition. I used to play open mic bars and clean vans for a living, so when I had a shot at making an album I wanted it to be a good one, and I wanted people to remember my voice. Now my goal is to keep the music at a level that feels good, and to not to get too precious about things, you know? My perspective is still exactly the same as it was when I started out, it’s just that I’ve got more experience.

If you had to offer one piece of advice to the young musicians starting out now, what would it be?

You just have to find that thing in you that flows, and stick with that. You have to have a voice of some kind – something to say, something to offer – and whatever it is, it has to be your thing. There are a lot of people who try to be like other people, but there’s only one of you so you should try to be as individual as you can. Don’t listen to too many opinions because, at the end of the day, you’re the person who has to live with what you do.

November 2015